Analytics and the Art of Territory Conquest

In addition to doing data science at Apptimize, I play a lot of Go. The thing about Go players is this: once the game has ensnared us, we are forevermore compelled to think of everything else in its terms. That brings me to this post. Nancy, our CEO, asked me recently if I knew of any parallels between Go and analytics – to which I said, challenge accepted.

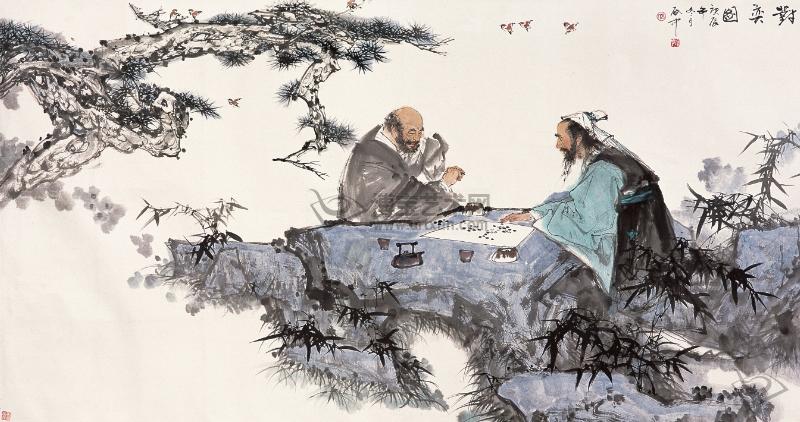

For those unfamiliar with the game, Go is a board game from ancient China, in which two opponents place stones on the intersections of a 19×19 board in a contest to claim territory. The rules are simple, but give rise to incredibly complex gameplay. In the professional leagues in East Asia, children must generally start training before the age of 10 to have a hope of making a living off the game. But, I digress. How does one think about analytics, and mobile A/B testing in particular, through the lens of Go?

Tesuji, or, Matching Tactics to Situations

In Go, there are generally two levels of play. At the strategic level, you might consider what area of the board to play in, the balance between your groups, and whether to gain influence or claim territory. At the tactical level, you might think about how to accomplish a specific objective such as saving a group, killing a group, ruining your opponent’s shape, or bolstering your own.

The moves used to accomplish such specific tasks are called tesuji, tactically appropriate responses. The ladder; the net; the throw-in; the placement; and more: each of them has a name and a specific function. When applied correctly, they are devastatingly effective, but in the wrong context, they might do nothing or even hurt you.

Analytics works the same way. Filtering and segmentation, for example, are two very important types of tesuji. Each field you might choose to filter or segment on is a tesuji of its own. If you are deciding which of two ads to run, filtering on location might be extremely important. If, instead, you want to know which of two design schemes to use, you might want to segment by gender. If you applied these tesuji to every single test you ran, however, it would be not merely ineffective but possibly harmful, because you would find many more false positives than you would have by looking at only the factors you found relevant.

Sente and Gote, or, Things Are Not Always As They Seem

Sente means “initiative,” and, generally speaking, you always want it when playing Go. The player with sente gets to decide the flow of play. If you lose it and fall into gote, you are forced to follow your opponent around, always getting the worse end of every exchange because you did not initiate it. So, it stands to reason that when you have a sente move, you should make it.

However, there’s a catch: some moves are only sente at the beginning. Although you’ll start in sente, forcing your opponent to respond, the next few moves will leave you with a potentially crippling weakness that you’ll have to guard in gote. These moves are called sente no gote, and instead of these, you’d far rather do the opposite: gote no sente, in which you make a move that does not demand an immediate response, but threatens a large follow-up if ignored.

In A/B testing, drastic UX changes have a habit of being sente no gote. Our marketing expert Lynn, in her recent guest post, brought up logo changes and annoying buttons as a couple of examples. Although these changes might draw attention initially, leading to positive results, their effects would lessen or even reverse over time as people got used to them. Backend changes such as algorithm tweaks are more likely to be gote no sente: a small lift at first, but increasing over time as users experience the full benefit of the invisible change.

Weak Groups, or, The Importance of Staying Focused

In Go, a collection of stones that lives or dies as one unit is called a group. The more of them you have, the more energy you must spend reinforcing and supporting them, and the more dangerous it becomes to create new ones. In fact, Go players have a saying: “Five groups live, but the sixth dies.” This pattern arises because there are practical limits on what a player, no matter how good, can accomplish with one move. Making matters worse, a battle between two groups naturally makes the fighting groups stronger while making the surrounding groups weaker. If you have too many groups, eventually you’ll have to choose which to let die, as with a fork in chess or the Green Goblin’s bridge drop in Spider-Man.

In Go, strong players often try to exploit the presence of weak groups by launching a splitting attack that threatens both. In products, the world works a bit differently. Bad features don’t die; they just fade away. But, given that they steal space and attention from their surroundings, it would be better to kill them.

In your product, every unnecessary feature is a weak group. Imagine if Facebook’s “Poke” still took up valuable screen real estate! On its own, it might be mildly entertaining, but it would also detract from the effectiveness of everything else Facebook put on your homepage. Whether it’s feature creep or leaving in old, unnecessary functionality, the effect of weak groups in your app is the same: expending the precious user attention that you should be directing to the best parts of your product.

Tsumego, or, Generalizing Patterns

Playing Go and getting better at Go are two correlated but very different things. Most of the knowledge a Go player has of the game, they acquire through deliberate practice: reviewing games, reading and watching lectures, learning joseki and fuseki and tesuji, and, most importantly, doing tsumego. Tsumego are well-defined life-and-death problems, usually with a single best solution and a number of tempting but wrong alternatives. When you practice them, you internalize the patterns that will help you figure out what to evaluate in a real game.

Many players, when first studying tsumego, protest that the problems they’re solving would never occur in a real game. True, perhaps, but these exercises teach the principles involved in solving real-game problems in a distilled, precise form. Once you understand these principles, you can generalize them to the infinite variety of positions that occur in your own games.

When you perform a statistical test, you are solving a tsumego. The test is well-defined, contained, and precise. When you figure out which variation works best, you learn something about that part of your app, but you also learn general principles if you choose to. Maybe some users are more responsive to a certain UI than others – try filtering by screen size or platform. Maybe a subset of your users are more inclined to respond to a certain product – try segmenting by age or gender. The value of each test lies not only in its results, but also in its lessons.

A Matter of Perspective

I could make as many parallels as I have terms, but I’ll stop here for the sake of brevity. Overall, the most important principle is the same between Go and analytics: the right move only becomes apparent after looking from many angles. Just as a move may be locally optimal but globally lacking, evaluating a change in one part of the app may depend on how it affects the others. Similarly, just as a move may look promising until you read farther, the data may lead one way on the surface and another when you dig deeper. So, next time you’re trying to outwit your competitors, remember these Go-inspired lessons, and test strategically.

Thanks for

reading!

More articles you might be interested in:

App UX Analytics: The Key to Understanding your Users’ Behavior

This is a guest post written by Alon Even of Appsee. In the highly competitive world of apps, you need to fully understand the user experience. You need to know how users are using your app. You need to know...

Read MoreHotelTonight A/B Tests with Apptimize

HotelTonight, a booming mobile-first travel company, is doing things that their competitors can’t do. This is due to their focus on customer experience, desire for innovation, and attention to data. In this video, Director of Product, Audrey Tsang, talks about...

Read More5 Things Analytics Won’t Tell You About Your Mobile App

1. Is your conversion rate good? 2. Are your engagement and retention rates good? 3. Are the new features and design changes you make actually improving your top goals? 4. How can you grow your user base? 5. What actually...

Read More